Clean Coding

Source: Jonathan Fulton

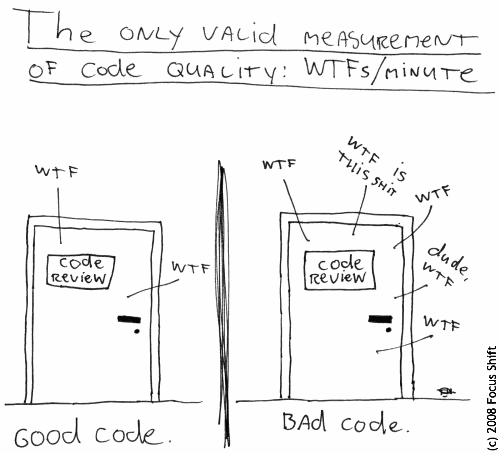

A few years ago at VideoBlocks we had a major code quality problem: “spaghetti” logic in most files, tons of duplication, no tests and more. Writing new features and even minor bug fixes required a couple of Tums at best and entire bottles of Pepto-Bismol and Scotch far too often. Our WTFs per minute were sky-high.

Today, the overall quality of our codebases are significantly better thanks in large part to a deliberate effort to improve code quality. A couple ago when we identified the problem, we read Robert Martin’s Clean Code as a team and did our best to implement his recommendations and even introduced “clean code” as a core cultural tenant for the engineering team. I highly recommend doing both as you start scaling. Implementing “clean code” practices appropriately will double productivity in the long run (at a bare minimum) and significantly improve moral on the engineering team. Who wants to be in the room on the right given the choice?

Out of all the ideas we implemented from Clean Code and other sources, five provided at least 80% of the gains in productivity and team happiness.

- “If it isn’t tested, it’s broken”

Write lots of tests, especially unit tests, or you’ll regret it. - Choose meaningful names

Use short and precise names for variables, classes, and functions. - Classes and functions should be small and obey the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

Functions should be no more than 4 lines and classes no more than 100 lines. Yep, you read that correctly. They should also do one and only one thing. - Functions should have no side effects

Side effects (e.g., modifying an input argument) are evil. Make sure not to have them in your code. Specify this explicitly in the function contracts where possible (e.g., pass in native types or objects that have no setters)

Let’s walk through each one in detail so you can understand and start applying them in your day-to-day life on an engineering team.

1. “If it isn’t tested, it’s broken”

I started regularly repeating this sentence to our engineers as we encountered bugs that should’ve been caught by (nonexistent) tests. You too will prove the quote true again and again unless you build a culture of testing. Write a lot of tests, especially unit tests. Think very hard about integration tests and make sure you have a sufficient number in place to cover your core business functionality. Remember, if there’s not test coverage for a piece of code you’ll likely break it in the future without realizing it until your customers find the bug.

Repeat “if it isn’t tested, it’s broken” to your team over and over until the message sinks in. Practice what you preach, whether you’re a brand new software engineer straight out of school or a grizzled veteran.

2. Choose meaningful names

There are two hard problems in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.

You may have heard this quote before and it couldn’t be more relevant to your day-to-day life on an engineering team. If you and your team aren’t good at naming things in your code, it will become an unmaintainable nightmare and you won’t get anything done. You’ll lose your best developers and your company will soon go out of business.

Seriously though, friends don’t let friends use bad variable names like data, foobar, or myNumber and they most certainly don’t let them name classes things like SomethingManager. Make sure your names are short and precise, but when in conflict favor precision. Strongly optimize around developer efficiency and make it easy to find files via “find by name” IDE shortcuts. Enforce good naming stringently with code reviews.

3. Classes and functions should be small and obey the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

Small and SRP go together like a chicken and an egg, a virtuous cycle of deliciousness. Let’s start with small.

What does “small” mean for functions? No more than 4 lines of code. Yep, you read that correctly, 4 lines. You’re probably closing the tab right now but you really shouldn’t. It seems somewhat arbitrary and small and you’ve probably never written code like that in your life. However, 4-line functions force you to think hard and pick a lot of really good names for sub-functions that make your code self-documenting. Additionally, they mean you can’t use nested IF statements that force you to do mental gymnastics to understand all the code paths.

Let’s walk through an example together. Node has an npm module called “build-url” which is used for doing exactly what it’s name suggests: it builds URLs. You can find the link to the source file we’re going to look at here. Below is the relevant code.

Notice that this function is 35 lines long. It’s not too hard to understand but it could be significantly easier to reason about if we apply our “small” principle to factor out helper functions. Here’s the updated and improved version.

You’ll notice that while we didn’t adhere strictly to the 4 lines per function rule, we did create several functions that are relatively “small”. Each one does exactly one task that’s easy to understand based on it’s name. You could even unit test each of these smaller functions independently if you wanted, as opposed to only being able to test the one large buildUrl function. You may also notice that this methodology produces slightly more code, 55 lines instead of 35. That’s perfectly acceptable because those 55 lines are a lot more maintainable and easier to read the the 35 lines.

How do you write code like this? I personally find it easiest to write the list of steps down that you need to accomplish the task you’re hoping to do. Each of these steps might be a good candidate for a sub/helper function. For instance, we could describe the buildUrl function as follows:

- Initialize our base url and options

- Add the path (if any)

- Add the query parameters (if any)

- Add the hash (if any)

Notice how each of these steps translates almost directly into a sub-function. Once you get in the habit, you’ll eventually write all of your code using this top-down approach where you create a list of steps, stub the functions, and continue recursively like this into each of the sub-functions creating a list of steps, stubbing, and so on.

Moving on to our related concept, the Single Responsibility Principle. What does this mean? Quoting directly from Wikipedia:

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) is a computer programming principle that states that every module or class should have responsibility over a single part of the functionality provided by the software, and that responsibility should be entirely encapsulated by the class. All its services should be narrowly aligned with that responsibility.

Robert Martin in Clean Code provides a parallel definition:

The SRP states that a class or module should one, and only one, reason to change.

Let’s say we’re building a system that needs to a certain type of report and display it. A naive approach might be to build a single module/class that stores the report data as well as the logic for displaying the report. However, that violates SRP because there are two high level reasons to modify the class. First, if the report fields change, we’ll need to update it. Second, if the report visualization requirements change, we’ll need to update the class. Therefore instead of a single class to store both the data and the logic for rendering the data, we should split those concepts and areas of ownership into two different classes, say ReportData and ReportDataRenderer or something similar.

4. Functions should have no side effects

Side effects are truly evil and make it extremely difficult to create code without bugs. Check out the example below. Can you spot the side effect?

The function as named is designed to look up a user by email/password combination, a standard operation for any web application. However, it also has a hidden side effect that you do not know about as the function consumer without reading the implementation code: it logs the user in, which creates a login token, adds it to the database, and sends a cookie back to our user with the value so they’re subsequently “logged in”.

There are many things wrong with this.

First, the function contract/interface is not easily understood without reading the implementation code. Even if the login side-effect is documented, though, it’s still not ideal. Engineers tend to use intellisense in modern IDEs so won’t think they need to read the documentation based on the simple function name. They’ll tend to use the function solely to fetch the user object, failing to realize that they’re adding a cookie to the request which can lead to all sorts of fun hard-to-find bugs.

Second, testing the function is fairly challenging given all the dependencies. Verifying that you can look a user up by email/password requires mocking out an HTTP response as well as handling the writes to the login token table.

Third, the tight coupling between user lookup and login inevitably won’t satisfy all use cases in the future, where you’ll likely need to look up a user or login a user independently. In other words, it’s not “future proof”.

In summary, make sure to remember and apply these four “clean code” principles to dramatically improve your team’s productivity:

- “If it isn’t tested, it’s broken”

- Choose meaningful names

- Classes and functions should be small and obey the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

- Functions should have no side effects